Analysis of the Medical and Scientific Content of the Edwin Smith Papyrus Spinal Inju

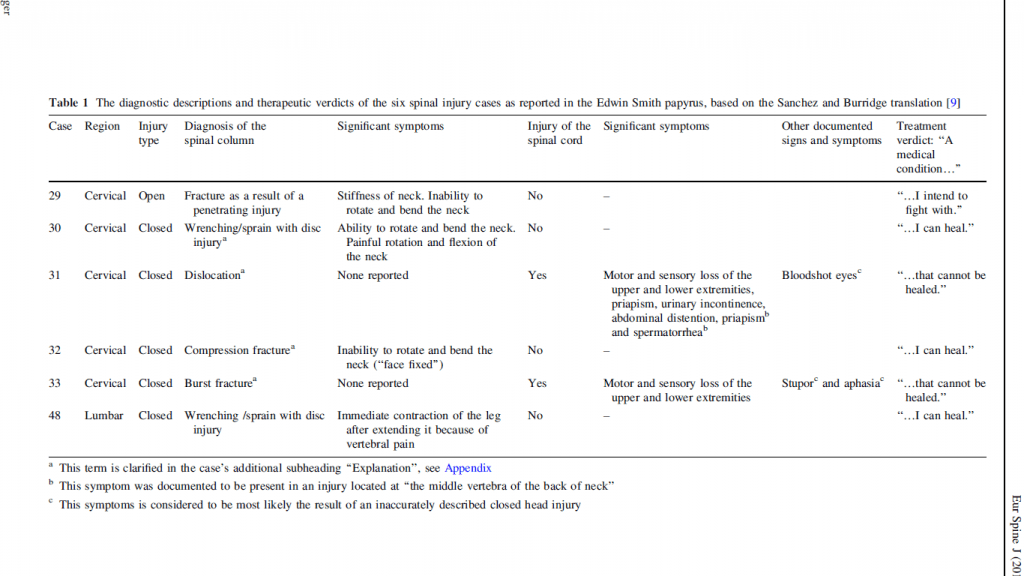

The document consists of the first part of a textbook on bodily injuries which are described systematically from head to toe. The book consists of a series of case reports of which the first 27 deal with injuries to the head. Then come 6 cases of injuries to the throat and neck of great interest to us, 2 cases of injury to the clavicle, and 12 cases with injuries to the humerus, sternum, and shoulders. The last case, case 48, is the most interesting dealing with the spine and further cases of injury to the spine, chest, abdomen, and lower limbs. Six cases concern the most, and these are cases 29 to 33, Figure 1 and case 48. All are similar in form with a title, a description of the examination of the case, followed by a statement of the diagnosis, and ending with recommendations for treatment, if treatment is indicated, otherwise the unfavorable outcome is stated.

- Six Selected Case Reports of Spinal Cord Injuries:

Case 29: Instructions concerning a gaping wound in a vertebra of his neck

Examination: If thou examine a man having a gaping wound in a vertebra of his neck, penetrating to the bone, (and) perforating a vertebra of his neck; if thou examine that wound, (and) he shudders exceedingly, (and) he is unable to look at his two shoulders and his breast.

Diagnosis: Thou should say concerning him: ‘(One having) a wound in his neck, penetrating to the bone, perforating a vertebra of his neck, (and) he suffers with stiffness in his neck. An ailment with which I will contend.’

Treatment: Thou should bind it with fresh meat the first day. Now afterward moor (him) at his mooring stakes until the period of his injury passes by.

Modern commentary: This must surely be a wound sustained in battle and inflicted by a

spear or similar pointed weapon. There is an open (gaping) wound with penetration of the weapon to the vertebra which is injured. However, the spinal cord is not injured since there was ‘stiffness’ of the neck but no paralysis or sensory loss as described in subsequent cases. The surgeon considered the prognosis favorable and the wound was to be bound up with fresh meat. Spinal and orthopedic surgeons please note that the phrase ‘moor him at his mooring stakes’ does not mean skeletal traction but was an idiom meaning to continue the original treatment without further prescription.

Case 30: Instructions concerning a sprain in a vertebra of his neck

Examination: If thou examine a man having a sprain in a vertebra of his neck, thou should say to him: ‘Look at thy two shoulders and thy breast.’ When he does so, the seeing possible to him is painful.

Diagnosis: Thou should say concerning him: ‘One having a sprain in a vertebra of his neck. An ailment which I will treat.’

Treatment: Thou should bind it with fresh meat the first day. Now afterward thou should treat (with), (and) honey every day until he recovers.

Ancient Commentary: As for: ‘A sprain,’ he is speaking of a rending of two members,

(although) it (= each) is (still) in its place.

Modern Commentary: The form of this surgical textbook is to proceed in each part of the body, which is serially dealt with, from slight to severe injuries. This case is more serious than that preceding since two vertebrae are involved. The translation uses the word ‘sprain’ and the Egyptian equivalent is only known in this papyrus, where, however, it occurs several times. The writer of the ancient commentary was not entirely familiar with the word ‘sprain’ but helps us to a modern diagnosis of a fracture or a fracture dislocation of the spine without displacement. There is no mention of an open wound. A favorable prognosis is given with a recommended treatment.

Case 31: Instructions concerning a sprain in a vertebra of (his) neck

Examination: If thou examine a man having a dislocation in a vertebra of his neck, should thou find him unconscious of his two arms (and) his two legs on account of it, while his phallus is erected on account of it, (and) urine drops from his member without his knowing it; his flesh has received wind: his two eyes are blood-shot; it is a dislocation of a vertebra of his neck extending to his backbone which causes him to be unconscious of his two arms (and) his two legs. If, however, the middle vertebra of his neck is dislocated, it is an emissio seminis (discharge of semen) which befalls his phallus.

Diagnosis: Thou should say concerning him; ‘One having a dislocation in a vertebra of his neck, while he is unconscious of his two legs and his two arms, and his urine dribbles. An ailment not to be treated.’

Ancient Commentary:

- As for: ‘A dislocation (wnh) in a vertebra of his neck, ‘he is speaking of a separation of one vertebra of his neck from another, the flesh which is over it being uninjured; as one says, ‘It is wnh,’ concerning things which had been joined together, when one has been severed from another.

- As for; ‘It is an emissio seminis (discharge of semen) which befalls his phallus,’ (it means) that his phallus is erected (and) has a discharge from the end of his phallus. It is said: ‘It remains stationary’ (MN s’w), when it cannot sink downward (and) it cannot lif upward.

- As for: ‘While his urine dribbles,’ it means that urine drops from his phallus and cannot hold back for him.

Modern Commentary: This is one of the most interesting cases in the whole papyrus and displays a knowledge of anatomy, physiology, neurology, and pathology. The ancient surgeon notes that dislocation of the vertebrae in the neck is accompanied by loss of sensation (unconscious of) of the arms and legs, lack of control of passage of urine, erection of the phallus and ejaculation of semen. The explanation in the ancient commentary of a dislocation without an open wound is remarkably clear. The description in Examination has aroused much speculation. It seems to indicate that the author distinguished between spinal injuries at two sites one possibly low down in the cervical spine associated with a cord lesion and another type affecting the ‘middle’ cervical vertebrae and causing penile erection and ejaculation. Treatment is not recommended which opinion is stated immediately after the description of quadriplegia with bladder incontinence. The phrase ‘his flesh has received wind’ probably means abdominal distention, and the phrase ‘his eyes are blood shot’ refers to vasodilation due to paralysis of vasomotor control.

Case 32: Instructions concerning a displacement in a vertebra of his neck

Examination: If thou examine a man having a displacement in a vertebra of his neck, whose face is fixed, whose neck cannot turn for him, (and) thou should say to him: ‘Look at thy breast (and) thy two shoulders,’ (and) he is unable to turn his face that he may look at his breast (and) this two shoulders, (conclusion follows in diagnosis).

Diagnosis: Thou should say concerning him: ‘One having a displacement in a vertebra of his neck. An ailment which I will treat.’

Treatment: Thou should bind it with fresh meat the first day. Thou should loose hi bandages and apply grease to his head “as far as” his neck, (and) thou should bind it with. Thou should treat it afterward [with] honey every day, (and) his “relief” is sitting until he recovers.

Ancient Commentary. As for: ‘A displacement in a vertebra of his neck,’ he is speaking concerning a sinking of a vertebra of his neck [to] the interior of his neck, as a foot settle into cultivated ground. It is a penetration downward.

Modern Commentary: This fourth case describes cervical spinal injury with displacement of a vertebra but not apparently with involvement of the spinal cord. A good prognosis is given and treatment is recommended. The ancient scribe made in this case an interesting copying error. Beginning line four he omitted the customary ‘Thou should say concerning him’ and then, observing his error, inserted the words at the top of the column. At the left end of line three he placed, in red ink, a cross, creating the first example of the use of the asterisk (mark).

Case 33: Instructions concerning a crushed vertebra in his neck

Examination: If thou examine a man having a crushed vertebra in his neck (and) thou finds that one vertebra has fallen into the next one, while he is voiceless and cannot speak; his falling head downward has caused that one vertebra crush into the next one; (and) should thou find he is unconscious of his two arms and his two legs because of it, (conclusion follows in diagnosis).

Diagnosis: Thou should say concerning him: ‘One having a crushed vertebra in his neck; he is unconscious of his two arms (and) his two legs, (and) he is speechless. An ailment not to be treated.’

Ancient Commentary:

- As for: ‘A crushed vertebra in his neck,’ he is speaking of the fact that one vertebra of his neck has fallen into the next, one penetrating into the other, there being no movement to and fro.

- B. As for: ‘His falling head downward has caused that one vertebra crush into the next, ‘it means that he has fallen head downward upon his head, driving one vertebra of his neck into the next.

Modern Commentary: This case is the most serious so far. A man has fallen head downwards and suffered a crush fracture of a cervical vertebra with compaction of one vertebra into the next. There is no abnormal movement but spinal cord damage is evident. The brain is affected (speechless) and possibly there is vertebral artery obstruction or an accompanying head injury. Prognosis is bad and no treatment is indicated.

Case 48: Instructions concerning a sprain of a vertebra [in] his spinal column

Examination: If thou examine [a man having] a sprain in a vertebra of his spinal column, thou should say to him: ‘Extend now the two legs (and) contract them both (again).’ When he extends them both, he contracts them both immediately because of the pain, causes in the vertebra of his spinal column in which he suffers.

Diagnosis: Thou should say concerning him: ‘One having a sprain in a vertebra of his spinal column. An ailment which I will treat.’

Treatment: Thou should place him prostrate on his back; thou should make for him (Here the scribe ceased copying in the middle of a word and the document ends)

Modern Commentary: The great interest of this last incomplete case report is swamped by our regret that we have none to follow and have lost descriptions of many thoracic, lumbar-sacral, and possibly cauda equina lesions, doubtless with many interesting observations of anatomy, physiology, neurology, and neuropathology. What survives here is of remarkable interest. A case of spinal injury is being examined, and the patient is being asked to extend and flex the legs. The case is an incomplete spinal cord lesion, a good prognosis is stated, and an interesting treatment, devised 5,000 years ago is about to be described when the document ends [1].

References:

1 Hughes, J.T.: ‘The Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus: an analysis of the first case reports of spinal cord injuries’, Spinal Cord, 1988, 26, (2), pp. 71-82

2 van Middendorp, J.J., Sanchez, G.M., and Burridge, A.L.: ‘The Edwin Smith papyrus: a clinical reappraisal of the oldest known document on spinal injuries’, European Spine Journal, 2010, 19, (11), pp. 1815-1823